"The overriding challenge for our generation is to build a new economy–one that is powered largely by renewable sources of energy, that has a much more diversified transport system, and that reuses and recycles everything." –Lester R. Brown, Plan B 3.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization

The high cost of living and limited economic opportunities in Iran are a boon to birth control, as couples take steps to keep their families small. But the Iranian Parliament has recently debated punishing people who promote contraception. And on June 24, 2014, it voted 106 to 73 in favor of making it illegal to perform sterilization operations. Whether or not this becomes law, the discussion signifies a dramatic about-face from when the government offered free vasectomies.

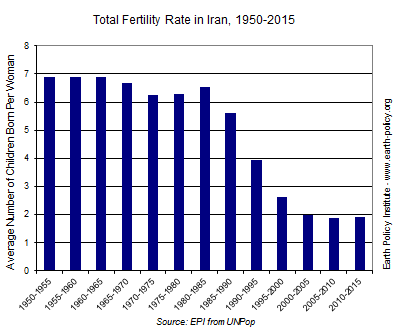

Iran is often hailed as a population success story. Encouraged by an extensive family planning and education campaign supported by religious clerics, average fertility rates there fell from over six children born per woman in the early 1980s to two children during the first years of this century. In just one generation, Iran accomplished a demographic transition that took Western Europe centuries to achieve. While Iranian leadership has recently reverted to pro-natalist rhetoric and policies, urging women to stay home and have more babies, it is unlikely that the highly educated and economically stressed young population will revert to the high birth rates of their grandparents’ time.

As early as 1967, family planning was recognized as a human right in Iran, enshrined in a national policy introduced by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The aim was to accelerate economic growth and improve the status of women, encouraging them to join the workforce. And although religious conservatives preached against the use of birth control, many women—particularly those living in cities—embraced the ability to control the number and spacing of their children with oral contraceptive pills. A 1973 law, which went into effect in 1976, loosened restrictions on male and female sterilization. In the mid-1970s, family planning promotion hit the mass media.

Then came the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Because of their association with western ideals, family planning programs were dismantled. The government encouraged procreation, paying allowances to families for each child. During the 1980–88 war with Iraq, more babies meant more soldiers, and revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini extolled the benefits of large families. Iran’s population growth rate soared to near 4 percent, according to U.N. statistics—one of the world’s highest. By 1986, nearly half of Iran’s population was under the age of 15. (See data.)

After the war ended, the economy faltered. People in overcrowded and polluted cities had difficulty finding employment. Iran’s family planning program was revived, with the goal of limiting family size to three children. Hefty resources were allocated to make a wide variety of modern contraceptives available free of charge to all married couples. In 1990, the High Judicial Council affirmed that vasectomies were consistent with Islamic principles, making them socially acceptable again. Farzaneh Roudi of the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) writes that a national family planning bill passed in 1993 called for an intensive population awareness campaign. Schools included courses on population, and the popular media were used to spread the message of “fewer children, better life.”

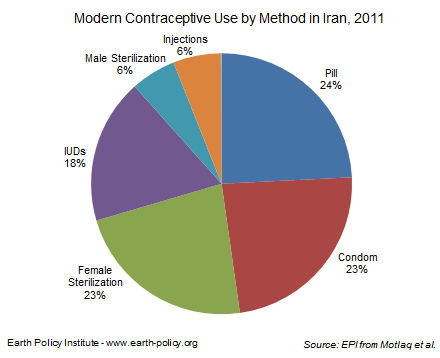

All this happened when female education was fast on the rise. The campaign stretched from the cities to the countryside, with rural “health houses” integrating family planning into primary health care. Religious leaders preached about the social benefits and responsibility of having smaller families, and issued fatwas—religious edicts with the strength of court orders—encouraging contraception, which engaged couples would learn about in a course they had to take before getting a marriage license. By 1994, just over half of childbearing-aged women in Iran were using modern contraception, up from 30 percent in 1989. The birth control pill was the most popular choice. An additional 19 percent used traditional methods to limit family size.

Family planning has continued to spread. A 2011 survey indicates that some 82 percent of Iranian women are trying to control their fertility, with over 70 percent of them using modern contraceptive methods. Condoms have become nearly as popular as birth control pills, an indication of Iranian men’s increasing role in limiting family size, helped along by large government purchases from Iran’s condom factory.

Yet the family planning policy pendulum has swung back the other way, as evidenced by the recent Parliamentary vote. In 2006, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad told the Parliament that two children were not enough and that women should focus on raising more. In 2010, he reinstated payments for each new child. By 2012 the Health Ministry’s “population control” budget was eliminated, devoted instead to growing larger families. Birth control is no longer subsidized, though a vibrant private industry means that it is still widely available.

Control over personal fertility is once again viewed by some conservatives as a dangerous western influence. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamanei called the 1990s' actions that led to women controlling the size and the timing of their families, including his own role in the family planning campaign, a “mistake.” The current president, Hassan Rohani, has not been particularly vocal on population, but in May 2014, Ayatollah Khamanei released a 14 point plan to raise population growth rates. The talk now is that Iran’s population should double to 150 million by 2050. The old television messages that urged families to stop at two children have been replaced; the Economist reports on a recent state-run broadcast of a prominent cleric urging families to have at least five children—like the Prophet Mohammed’s family—but a dozen would be even better.

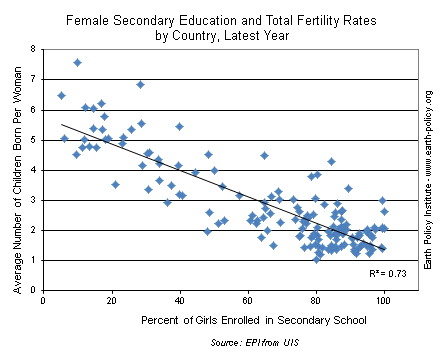

Currently the highest fertility rates in the Middle East are in Yemen, a failing state by many measures, where women have four children or more on average (down from nearly seven at the end of the 1990s). In the last nationwide survey in 2006, just 19 percent of women in Yemen used modern contraceptives. Only half of Yemeni women know how to read, and while all the boys went to primary school in 2012, at least 58 percent of girls stayed home. Contrast that with Iran, where schooling is largely universal and women outnumber men at the university level. Some colleges in Iran have even introduced quotas to keep the male presence from falling further.

In country after country, when more girls are educated and stay in school longer, birth rates fall. With both traditional literacy and Internet use high in Iran (albeit an officially censored Internet), it will be hard to turn back the clock and send young Iranians rushing to have more children. PRB’s Roudi says that “Iran’s family planning program of the past two decades was successful because it met the needs of families. The new policy is solely top-down without considering peoples’ needs; that is why it won’t be successful.”

Nevertheless, anything that makes it harder to get reproductive health services and information could lead to an uptick in unplanned pregnancies and abortion. Abortion is illegal in Iran, punishable by a fine and imprisonment of up to five years, but it still happens in secretive and often unsafe conditions. Furthermore, there is a serious risk that if condoms become more expensive or hard to find, transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, could increase.

The thought of Iran’s population doubling quickly—further crowding cities, worsening traffic jams, overwhelming classrooms, and upping unemployment—once struck fear into Iranian leaders. The country's population is young, a relic from past ultra-high growth rates, and still growing at 1.3 percent a year, even as people leave in search of opportunity. If the current trend toward smaller families holds in spite of the urging to change course, Iran’s annual growth rate will drop below 0.5 percent by mid-century—a rate similar to that of a number of countries, including Japan and many in Western Europe, that have nearly stabilized their populations. While aging populations bring some problems, they pale in comparison to those that accompany overpopulation. Large numbers of young people with limited job prospects and uncertain futures can prove quite volatile, as recent history has shown. And further, water shortages are now considered a major security risk in Iran. With lakes shrinking and water tables falling from excessive withdrawals at the current population size, the safest path for Iran is to continue to move toward population stability.

Copyright © 2014 Earth Policy Institute

Print:

Print:  Email

Email